Addressing financial wellbeing with a systems based approach

This piece is a short summary of the recently released Amplify Insights: Financial Wellbeing report, produced by the Centre for Social Impact (CSI), UNSW, which can be found here. The report was written by Dr Jeremiah Brown (@jeremiahtbrown), and Dr Jack Noone (@drjacknoone). Jeremiah is a Research Fellow at CSI UNSW, and Jack is a Senior Research Fellow at CSI UNSW. This piece is adapted from the launch webinar for the report, which was held as part of the impact 2021 webinar series. You can view that launch webinar here.

Previous work from CSI has defined financial wellbeing as when a person is able to meet expenses and has some money left over, are in control of their finances and when they also feel financially secure, now and in the future.

Within this definition there are three interrelated dimensions:

Meeting expenses with some money left over: this includes having an adequate income to meet basic needs, pay off debts, cover unexpected expenses and have some money left over.

Being in control of your finances: this includes both feeling and acting in control of your finances.

Feeling financially secure: this includes not having to worry much about money and having a sense of satisfaction with your financial situation.

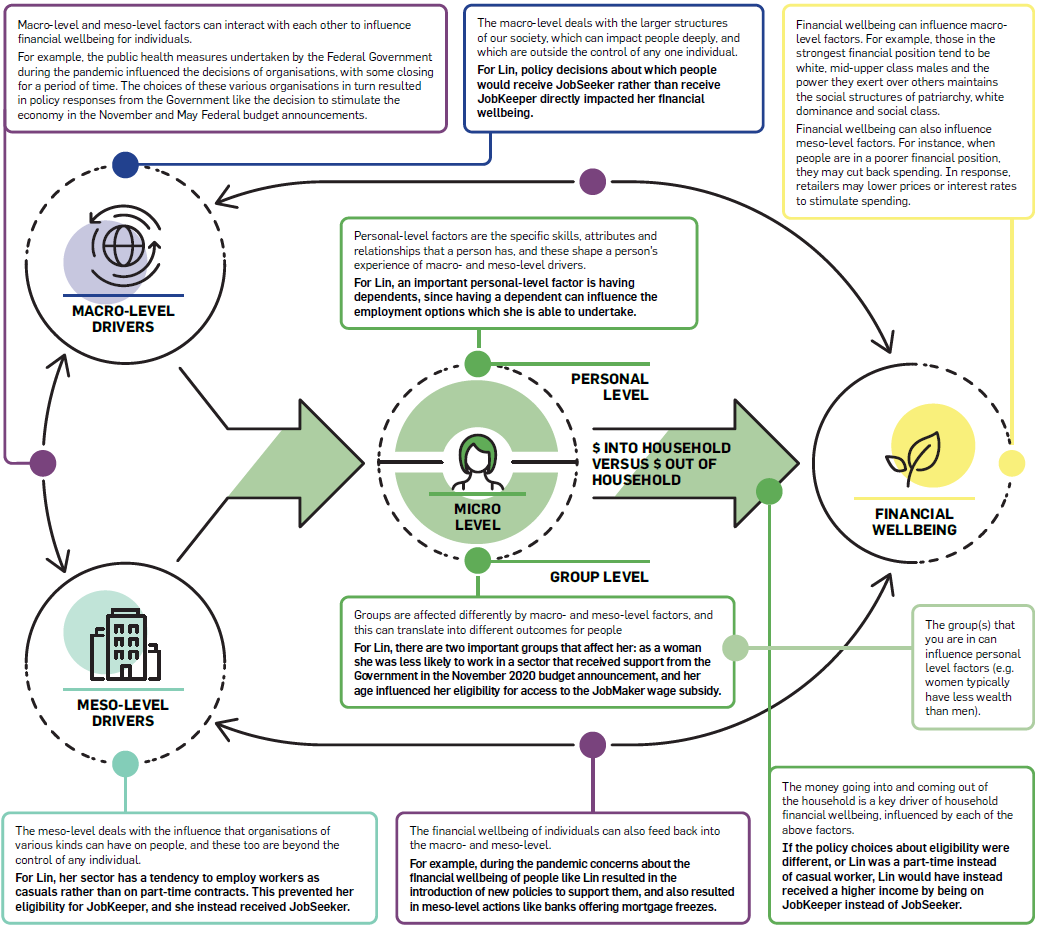

We argue throughout the report that these all depend on things that are external to us – that is, the system around us. When we talk about the financial wellbeing system, there are 3 different levels which we are talking about:

The Micro level: These are the factors related to financial wellbeing that occur at the individual or household level, and this can include both personal and group related things:

Personal factors are things you have some degree of control over – for example, the level of education you have.

Group factors are things that are related to the specific groups or cohorts you belong to, and typically you cannot control the impact that they have – for example, your age or gender.

The Meso level: These factors deal with the influence that organisations and institutions have on personal financial wellbeing.

The Macro level: These factors deal with the larger structures of our society and the influence that these structures can have on personal financial wellbeing.

Below we have included a table with a list of some of the different factors we discuss in the report.

The Macro and Meso level drivers feed into the experience of individuals at the micro-level. In turn, these all shape the money coming into a household and the money going out of the household. Meso and macro level factors can also influence each other – for example government policy which is a macro-level factor can change decisions that organisations make.

The important thing to understand is that not every driver or factor has the same impact on every household – and your personal context is a critical factor in how you experience the macro and meso-level drivers. For example, the pandemic was a macro-level event that had different effects on different households depending on who you were. The example we use in the report highlights how different factors can influence just one individual.

Lin was a 36-year-old hospitality worker, and she is a single parent living in Melbourne, Victoria, with a 9-year-old son. Lin is highly financially savvy – with a high level of financial capability. She knows her rights and what she is eligible for in terms of accessing government support. Unfortunately, during the second Melbourne lockdown the business Lin worked at was forced to shut during the lockdown.

As is common in her sector, Lin is a casual employee, which meant that she was not eligible for JobKeeper. Like many other casual employees Lin lost her job and moved onto JobSeeker which has a lower rate of payment than JobKeeper – during the later stages of the lockdown the gap for Lin was $338 per fortnight.

Her son was at home because schools were closed through the lockdown, and as the primary caregiver Lin needed to look after her son which limited her work availability. Because her son was 9 – instead of 8 – Lin missed out on being able to access support for childcare for her son. Lin needed to look for work, but because she was looking in a new sector where she was less experienced, it was harder for her to find employment.

Lin’s 36 years old. If she was 35, then eligible employers that hired her would qualify for the $100 JobMaker Hiring Credit. If she was 29, that subsidy would increase to $200 per week. Because of this Lin is a less attractive employee than someone who would qualify for the subsidy.

In the diagram below you can see the different ways across the financial wellbeing system that Lin was impacted through the pandemic.

It is helpful to consider a different scenario for Lin, and through that see how her financial wellbeing might be different. Starting at the macro level – because Lin’s eligibility for either JobKeeper or JobSeeker was based upon a distinction made in a national policy – it is easy to imagine a different scenario where the rate for JobSeeker and JobKeeper were the same, or that eligibility was not based upon the type of contract (so being a casual didn’t matter). In both instances Lin would have a higher income throughout the pandemic.

It is notable that we have actually seen different eligibility criteria in the newer COVID-19 Disaster Payment measures for the different lockdowns that are currently occurring across Australia. It is also noteworthy that some groups are eligible for different levels of support (like those currently receiving an income support payment).

At the meso level, the preference of her sector to use casual employment influenced her eligibility for the support as well. If Lin was working in a different sector, it is easy to imagine that she instead had the right kind of contract and therefore was put onto JobKeeper instead of JobSeeker.

At the group level, her age and gender were relevant factors for multiple reasons. In terms of gender, gendered norms about caregiving meant that women were more likely to take on additional caretaking and work reduced hours during the pandemic – that happened in lots of different countries, not just in Australia. Her gender is also associated with the sector she is employed in, and the fiscal stimulus measures originally announced last year tended to be higher in sectors where men made up a higher share of the workforce. Her age also influenced her eligibility for the JobMaker hiring credit.

Finally, at the personal level, having a dependent influenced her capacity to look for work. If Lin did not have a dependent, there would have been a whole range of extra employment opportunities she might have been able to take up during the pandemic.

For Lin, if we change any one of these factors about her, it can change her level of financial wellbeing. And these are all largely outside of her control. For example, Lin cannot change her age and make herself eligible for JobMaker.

Returning to the definition of financial wellbeing above, all three parts of Lin’s financial wellbeing have been negatively impacted by the pandemic.

First of all, by losing her employment, Lin has had her ability to meet expenses impacted through a reduction in her income. Secondly, there are some parts of Lin’s financial situation which she is no longer in control of. Her ability to return to employment is determined in part by the continued impacts that the pandemic will have on the economy. It is easy to see how Lin would feel like this is outside of her control. Thirdly, the increased cases and latest wave of lockdowns right now highlight that the pandemic continues to have an ongoing effect on how we feel about our financial situations, and will impact people into the future.

Altogether this can help us to see that the key drivers of her financial wellbeing during the pandemic were outside of Lin’s control – and they continue to impact her future. Our example of Lin is made up, but lots of Australians have had their financial wellbeing impacted in similar ways by the pandemic. Improving financial wellbeing for those people requires an understanding that we need to address the factors that people cannot control – that means that we need structural changes.

But no single actor can make these structural changes on their own.

That is why in the report we are calling for a more coordinated response across the wider financial wellbeing ecosystem. There are already organisations with a collective system change approach and we have seen that being more coordinated can be impactful in creating change – like with the Raise the Rate campaign lead by ACOSS.

We are interested in building up our understanding of the different points of leverage in the system that different organisations have which can be used to drive change – and that means mapping the system. We need to continue working on the issues at the micro level that people are already addressing, but we also need to be more deliberate in changing the meso and macro level. This will help change the systems and structures around us and create positive financial wellbeing outcomes. Our next piece of work will be creating a detailed map of the system to understand the system from the perspective of people experiencing low financial wellbeing – and to understand how different organisations can help with that.

We are asking everyone with an interest in financial wellbeing to be part of a collective action. If you’re interested in being part of the conversation please get in touch with the research authors, Dr Jack Noone and Dr Jeremiah Brown. In particular, we would love to hear your answers to the following questions:

What are the micro, meso and/or macro level drivers of financial wellbeing that your organisation is trying to affect? Tell us what your organisation does.

If the social purpose ecosystem was to develop a coordinated response to improve financial wellbeing across Australia, what kind of role would you like to play?