Men’s behaviour change programs: good news and lessons from the Pacific

A ground-breaking faith-based program in the Pacific seems to be having significant, and hopefully longer-term, impacts on men’s violence and abuse, with several important lessons for similar programs elsewhere, writes Miranda Forsyth, ANU Pacific Institute Convener and Associate Professor at ANU’s School of Regulation and Global Governance.

A pilot program to address gender-based violence (GBV) in Vanuatu has shown promise to engender meaningful attitude and behaviour change. So far, the Men’s Behaviour Change (MBC) program has been delivered to about 50 men. A preliminary evaluation points to some of the early successes, and possible improvements.

MBC is a 10-session small group therapy program for perpetrators of violence (either self-identified or selected by community leaders to attend). The program aims to assist men to reduce and stop family and domestic violence. The sessions address attitudes and behaviours around abuse whilst creating opportunities for men to understand the impact of their violence on their partners and families. It also supports men to recognise they can change and have caring, healthy and equal relationships.

This training has a strong focus of working with men and perpetrators of violence to: 1) accept responsibility for their action; 2) see violence as a choice; and 3) provide practical tools and strategies to change their behaviour. A co-designer of the program, Kara Duncan-Hewitt, observed:

“A key and foundational part of this is to promote empathy, using experiential exercises to support those in power to have a heart-felt understanding of the victim’s experience and reality, in order to help shift and disqualify cultural and religious justification for the violence. Key to this exploration and uptake is education is the concept of spiritual abuse. To support this work, positive values of theology and culture are utilised to confront and challenge oppression and misuse of power, and further utilised to advocate for healthy and safe families and communities.”

The evaluation found participants and their families all highly valued the program, identifying it as having been transformative in the men’s changed attitudes and behaviour towards their spouse. Changed behaviours included greater engagement in housework and family life, less anger, more emotional connection with wife and family, and changed understandings about the relationship between men and women. One important tool was the STOP (Safe Time Out Please) sign, which was helping participants deescalate conflict in their homes.

Further, whilst Men’s Behaviour Change is in its infancy, it has potential for long-term change: the only participant interviewed who had done the program a year ago had sustained the changes, according to their partner.

Participants and facilitators identified four aspects of the program that they considered contributed to its success:

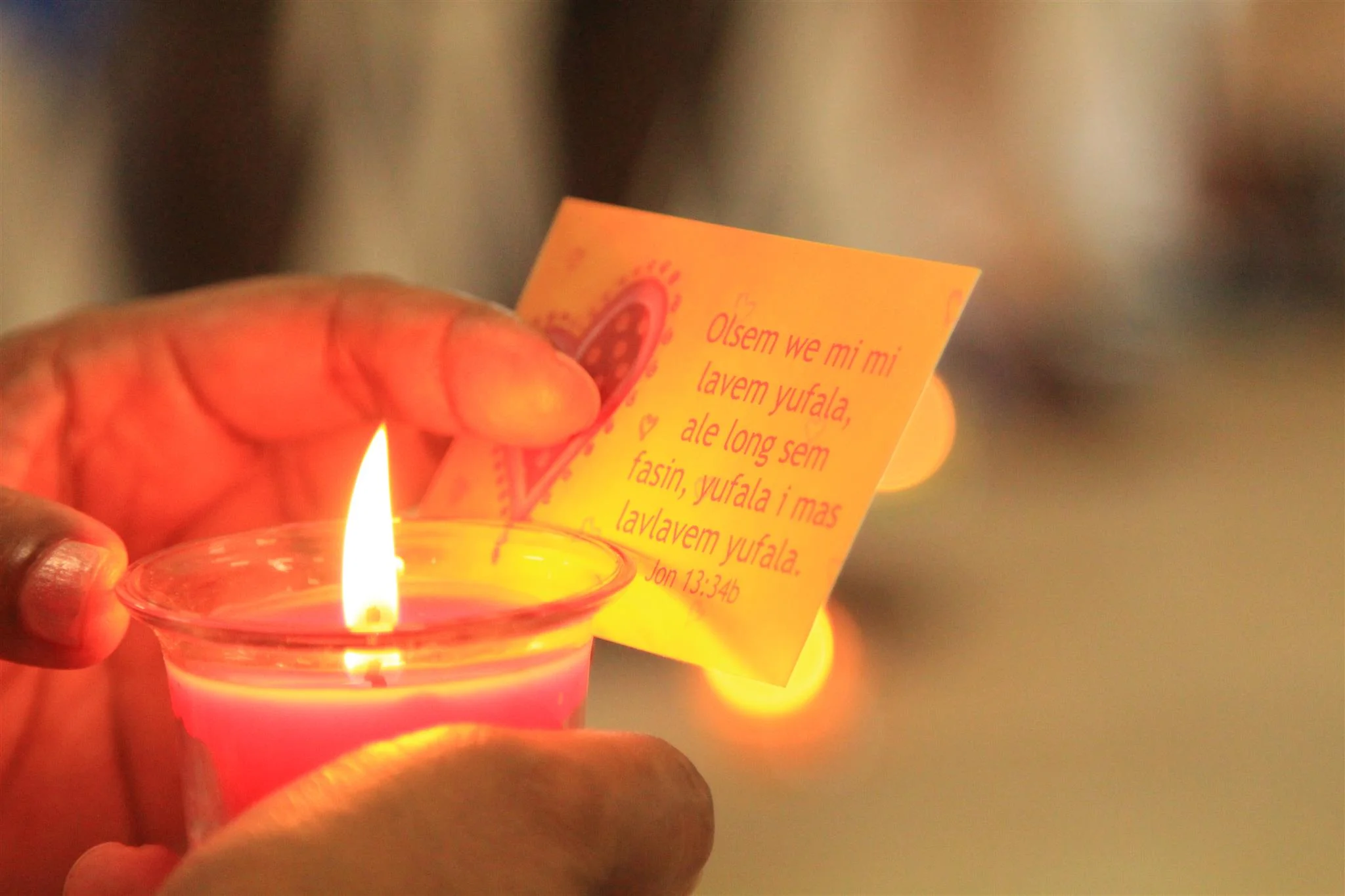

Christian framing (which provided authority and a familiar means through which to transmit messages);

Practical and staged steps suggested to deal with the real issues men face

Emotional engagement with the concepts it engendered in the participants; and,

Opportunity for men to both realise and acknowledge their past behaviour and to forge new paths for themselves.

In addition, the evaluation team also found a number of areas that could lead to improved outcomes, and increase the sustainability of behaviour change. These are:

Incorporate a restorative justice element into the program to better address apology and reconciliation through making space for victims’ voices.

Link the MBC into the work of probation officers to facilitate family and community reconciliations before parole is granted.

Bring spouses into the final stages of the program to ensure they understand the process their husband has been through and what can be done to help support the changes. As one participant said, the women are the ones who “receive back” the participants, so they need to be prepared. This is also an opportunity for the spouses to learn about tools and concepts they can utilise themselves.

Respond to the desire of participants and facilitators to share what they have learnt by preparing a number of specific components of the program that can be shared safely by them with their family/community.

These design elements are likely to resonate beyond Vaunatu, and should be considered when designing gender-based violence and behaviour change more broadly.

MBC was delivered as part of the REACH (Relationship Education about Choices and Healing), implemented by World Vision Vanuatu, and supported by the Australian Government through the Australian NGO Cooperation Program (ANCP). REACH built on the World Vision International “Channels of Hope for Gender” (CoHG) approach. This preliminary evaluation was funded by the Australian Government through the Gender Action Platform (GAP).